|

Published on The Nation (http://www.thenation.com)

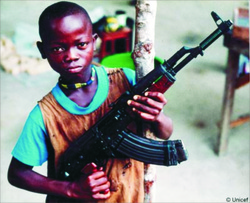

This article is a joint publication of TheNation.com and Foreign Policy In Focus [1]. After a closely contested election in El Salvador, the progressive Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) has emerged victorious, declaring a narrow victory over a right-wing opposition party that appealed to the military for intervention. The vote marks a hard-fought victory for the FMLN’s ambitious economic agenda, which has included a host of new social programs that have improved education and healthcare for millions of Salvadorans. But right-wing forces vigorously disputed the election—one that the Organization of American States called the most transparent in El Salvador’s history—and conditions imposed by Washington are threatening to undermine the country’s gains. While the US embassy officially maintained a neutral stance in the election, Washington is threatening to withhold development aid unless El Salvador adopts economic policies that are anathema to the ruling coalition of left and center forces that have been working together over the past five years. That threat could end up undermining the very programs that contributed to the FMLN victory in the March 9 poll. A Landmark Election Since taking power in 2009, the FMLN—a former guerrilla movement that became a political party in the early 1990s—has ushered in a host of popular social programs designed to improve living standards in El Salvador, where over a third [2] of the population lives in poverty. Before stepping down as minister of education to run for the presidency, FMLN president-elect Salvador Sánchez Cerén started a literacy program that reduced adult illiteracy from 18 percent in 2009 to 13 percent in 2012. The program, part of a broader push to make education accessible to all Salvadorans, functions on a $2 million budget and enjoys the support of over 40,000 volunteers. Other reforms include free school uniforms and a glass of milk every day for schoolchildren. Since 2009, the FMLN has been responsible for the implementation of a healthcare program that includes primary clinics throughout the country, regional hospitals and government funding for preventive health measures. Though healthcare has always been a right under the Salvadoran constitution, access had been restricted as part of privatization efforts—by 2006, in fact, 47 percent of Salvadorans had been pushed out of the healthcare system. Now, the Ministry of Health serves 80-85 percent of the population for free. The election also marks the first time that a former FMLN guerrilla commander has defeated a candidate from the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA)—a right-wing party founded by Roberto D’Aubuisson, the father of the US-backed Salvadoran death squads. The two parties were the main opponents in El Salvador’s civil war (1980-1992) and have been the country’s principal political parties since the 1992 peace accords. Sánchez Cerén’s victory suggests that the FMLN’s social programs and community organizing helped the party overcome the fear-based ARENA propaganda that was broadcast by the country’s right-wing-dominated media. In the run-up to the election, the Salvadoran Election Tribunal (TSE) quadrupled the number of voting centers, removed at least 50,000 deceased Salvadorans from the voter rolls and ensured that poll workers live close to voting centers, making it easier for them to identify fraudulent voters. These elections also marked the first time Salvadorans outside the country, who comprise over a third of the total population, have been able to vote. Yet in response to his electoral defeat, ARENA candidate Norman Quijano cried fraud, pushing back the official announcement of a winner by the TSE by several days. Quijano, who had previously declared victory with only 70 percent of votes counted, subsequently called on the Salvadoran military to “implement democracy,” adding ominously that ARENA was prepared for war. With a bloody civil war at the center of the country’s recent history, ARENA’s willingness to call upon the military to intervene is highly concerning. But David Munguía Payés, the minister of defense, rejected Quijano’s request, maintaining that the armed forces are “committed to respecting the electoral results issued by the Salvadoran Election Tribunal.” Days later, the TSE rejected ARENA’s demand to nullify the results and declared [3] Sánchez Cerén the winner. US Intervention In the past, the United States has given the Salvadoran oligarchy considerable support, including $6 billion in direct military assistance and training for the armed forces during the war. Though in recent years US intervention in Latin America has been less flagrant, Washington’s support for military interference in the region has continued. In 2009, when soldiers forced Honduran President Manuel Zelaya onto a plane to Costa Rica while still in his pajamas, the United States was the only country in the Americas not to classify the incident as a coup, allowing economic and military aid to Honduras to continue. The use of US foreign aid to exert control over the Americas is worrying for left-leaning governments in the region, especially as institutions such as the National Endowment for Democracy [4]—which financed the protests that sparked the attempted coup against former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez in 2002—continue to funnel money into similar projects, such as funding the party of Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo López. With Sánchez Cerén already likened to the late Chávez in much of the Salvadoran media, it will be difficult for the president-elect to continue the programs he was voted in to protect without fear of reprisal from the United States. By threatening to withhold foreign aid, the United States coerced El Salvador into enacting last year’s Public-Private Partnership law, which privatizes public services and assets to a degree that would cause an uproar if it were attempted in the United States. The law, an initiative of El Salvador’s bilateral trade agreement with the United States, was written by US Treasury Department advisers with the IMF, World Bank and the outgoing administration of President Mauricio Funes. The proposed partnership was unveiled in November 2011 during a visit by Barack Obama. Since its introduction, unions, to whom the new law guarantees no protections, have fiercely fought the Public-Private Partnership. If fully implemented, the law would threaten the job security of over 120,000 public-sector workers, who have seen wages drop as services have become privatized. The Bajo Lempa Community—a coalition of communities formed by ex-combatants and refugees from the civil war—warned in a statement that “the promises of employment and economic growth that were to accompany privatization, [US] dollarization and the signing of the Free Trade Agreement have never materialized. In their place, poverty, violence, [a] deteriorating environment and corruption have all increased.” The community has called the Public-Private Partnership “blackmail” and charged that it “violates the sovereignty of the Salvadoran state and its people.” Unable to stop the passage of the Public-Private Partnership, the FMLN bloc in the legislature voted for a revised version of the law that stopped the privatization of water, higher education, and healthcare. Now, US Ambassador to El Salvador Mari Carmen Aponte is making the privatization of these sectors a prerequisite for further funding from the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a US agency that provides foreign assistance on a competitive basis. After a close election, it will be difficult for the FMLN to forgo the Millennium Challenge Corporation money. When the Salvadoran people voted for the FMLN, they were voting for a platform of increased social programs and community control. The Public-Private Partnership foisted on the country by Washington could put these goals out of reach. With the US government leaning on El Salvador to accept a privatization package that would never be accepted in the United States—and the tenets of which were rejected by Salvadoran voters themselves—it appears that Washington still isn’t ready to let democracy flourish in Latin America.  On 26 September 2013, the UN Security Council adopted its first ever resolution on small arms and light weapons (SALW) with 14 votes in favor and 1 abstention (Russia). Among other things, the resolution recognizes the interrelationship between small arms and light weapons, women, peace and security, and human rights. Several of its paragraphs deal with women’s participation in small arms-related decision-making or with the link between small arms and gender-based violence. However, it must be noted that the top sellers of arms are represent by the permanent members of the UN Security Council. The policies of arms exporters are incongruent and contradictory, and often unquestioned. Read the full by Sarah van Gelder

Many of the legal and diplomatic processes that led to peace in other times of conflict haven't even been tried yet in Syria. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee's approval of military force in Syria makes military strikes against that country more likely. But key questions remain unanswered. Will military strikes help ordinary Syrians or harm them? Will more violence deter the use of chemical weapons and other war crimes in Syria and elsewhere, or exacerbate the problem? Have all other possibilities been exhausted, or are there peaceful solutions that haven't been tried? A quick review of the options suggests there are at least six strategies that could hold wrongdoers to account, deter war crimes of all sorts, and build peace. These strategies are based on an idea little discussed but deeply practical for our war-weary country and world. Instead of launching an assault on Syria, the United States could lead a "coalition of the willing" in rebuilding the tattered foundation of international law. This would lay the groundwork for peace, not only in Syria, but in all the lawless regions of the world. And it could do so without adding to civilian casualties, further destabilizing the Middle East, breaking the budget of the United States, and requiring yet more sacrifices by those who serve in the armed forces. For several reasons, this is the right time to turn to the rule of law. Why? First, this conflict does not lend itself to the cheap story used to whip up pro-war sentiment: the notion that military strikes will help the "good guys" in the opposition defeat the "bad guys" in the regime. The armed opposition in Syria includes many we don't want to support—especially those associated with Al Qaeda and other extremist groups. And the United States, too, has things to answer for—among other things its faulty claims about weapons of mass destruction in the lead-up to war in Iraq, the treatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, and civilian casualties of U.S. drone attacks in countries including Pakistan and Yemen. So building a case for war based on U.S. heroics in support of valiant upstarts against an evil despot just doesn't work. Our real choice is this: contribute to lawless violence or turn to the rule of law and civility. What would we do if we were to choose peace and the rule of law? Here are six approaches that would help build justice and peace in Syria and elsewhere. 1. Bring those guilty of atrocities to justice. With the backing of the U.N. Security Council, those responsible for the chemical weapons attacks and other war crimes should be brought to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for justice, whether they are part of the Syrian regime or members of opposition forces. "The use of chemical weapons by anyone is a war crime, and international law requires international enforcement," policy analyst Phyllis Bennis wrote in an email. "No one country, not even the most powerful, has the right to act as unilateral cop." The United States should strengthen the ability of the ICC to hold war criminals accountable by signing on and ratifying the statute that created the court in 1998. Even before bringing Assad and his allies to the ICC, Frank Jannuzi of Amnesty International told YES!, it's possible to punish these individuals with travel restrictions and targeted economic sanctions. 2. Call for a United Nations embargo on arms, military supplies, and logistical support for both Damascus and opposition forces. Stopping the flow of weapons from around the world into Syria is another important step toward peace. But it will involve complex diplomacy that has not yet been attempted. As Bennis writes, "Russia must stop and must push Iran to stop arming and funding the Syrian regime." But Russia and Iran are not the only culprits. Bennis continues: "The U.S. must stop and must push Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, Jordan and others to stop arming and funding the opposition, including the extremist elements." How can we exert pressure on those regimes? "That won't be easy," says Bennis. But we and the Russians do have leverage. For example, she says, Washington could tell the Saudis and Qataris that we will cancel all existing weapons contracts with them if they don't stop arming the opposition. 3. The U.N. Security Council should hold an international peace conference involving not only the Syrian government and opposition parties, but their backers from outside the country and those affected by the flow of refugees and arms. Non-state actors with an influence on the conflict should also be included, says a statement by the Friends Committee on National Legislation, a Quaker group. This should include Hezbollah, the Arab League, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, they say. Negotiators should aim for an immediate ceasefire, for the access needed to get humanitarian aid where it's needed, and for an end to the conflict. This is a tried-and-true solution that resolved the wars in Southeast Asia through the Paris Conference on Cambodia, and in the Balkans through the Dayton Peace Agreement. 4. Offer aid and support to the nonviolent movements within Syria, or, at least, don't undermine them. A resurgence in Syria's broad-based nonviolent movement for change that started in March 2011 is still a source of hope, according to Stephen Zunes, chair of Middle Eastern studies at the University of San Francisco. The opposition's turn from nonviolence to armed struggle resulted in higher civilian casualties, reduced defections from the Assad's forces, and contributed to the rise of anti-democratic elements within the opposition, Zunes says. He goes on to explain that nonviolent movements have a much better chance of building an inclusive democratic government. "Military intervention would demoralize and disempower those remaining in the nonviolent resistance who are daily risking their lives for their freedom," Zunes says, "while encouraging armed elements who—with their vanguard mentality, martial values, and strict military hierarchy—are far less interested in freedom and justice." 5. Provide the humanitarian aid desperately needed by the millions of displaced people. Humanitarian organizations are currently able to provide services within Syria only with great difficulty; the United Nations Security Council should insist that Damascus allow them access. And the international community, not just the countries housing the refugees, should cover the costs of caring for the displaced inside and outside the country. Yes, it's expensive. But a military strike would cost much more, as would the long-term costs society would incur from neglecting traumatized refugees. 6. Force the hand of Russia and China in the Security Council. Many people believe that Russia and China have vetoed efforts in the United Nations to condemn the Syrian regime or to impose sanctions on it. But all these governments have done, so far, is threaten to veto. Jannuzi says that the other 11 members of the Security Council should take the issue to a vote and force Russia and China to actually exercise their veto power. "That would at least give the rest of the international community the opportunity to say 'If that's your position, then what are you for?'" Jannuzi says. This would at least help to clarify the positions of these countries, an important step toward peace. Why the rule of law? By applying the rule of law through existing international institutions, we can work to isolate the wrongdoers on all sides of the conflict in Syria from their bases of support around the world. We can support those in Syria working for peaceful change and offer humanitarian assistance. And we will move beyond the limitations of responding to lawbreaking with violence. There's another benefit, too, of relying on the rule of law. Doing so would strengthen the institutions, like the United Nations and the International Criminal Court, designed to settle conflict without violence. That would mean we'd have more effective options available when future despots threaten to commit war crimes and crimes against humanity. To follow this path with credibility, though, the United States must itself live within the rule of law. That means, at the very least, refraining from launching into a war that violates international law. Only when a country is attacked, or when it has the support of a Security Council resolution, is a military assault on another country permitted. It might seem naïve to press for peace in a world where there is so much violence. But the belief that a few bombing missions and a quick exit could make a positive difference is in fact the naïve view. And Americans—traumatized, exhausted, and impoverished by war—have no stomach for the protracted military conflict with uncertain aims that is the more likely outcome. International law—fairly applied, patiently negotiated, with tough sanctions, and help for refugees—is in fact the most practical way to peace and justice for the people of Syria and beyond. Sarah van Gelder wrote this article for YES! Magazine, a national, nonprofit media organization that fuses powerful ideas and practice actions. Sarah is executive editor of YES! James Trimarco contributed reporting for this article. |

AuthorWILPF Portland Archives

January 2016

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed